Why

This one of the lesser-visited corners of Ecuador by foreigners, yet it offers beautiful countryside, rich history and a sense of Ecuador's lifestyle in the countryside.

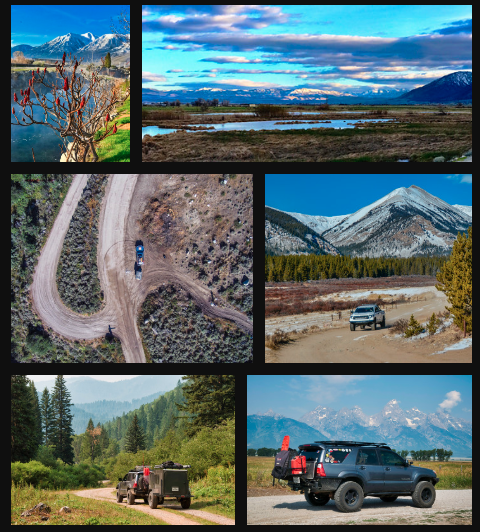

The Pan-American Highway, which stretches across the Americas from Alaska to Argentina, cuts straight through the Andes Mountains in Ecuador. Most overlanders driving the Pan-Am will cruise through this mountainous landscape. While a rewarding journey because of the stunning views, the drive is straightforward. For the unexpected and surprising part of the overland journey, you need to leave the asphalt and head into the countryside.

This is exactly what we did.

A turn-off took us to a hilly gold-mining town in the southwestern corner of Ecuador called Zaruma (or, officially, Villa Real de San Antonio del Cerro de Oro de Zaruma). This was a perfect road for overlanding, a narrow dirt road that required us to keep a slow pace bumpy but blissfully free of washboard as well as big trucks. It meandered through a green landscape of ferns with palm trees towering above all other vegetation.

In Zaruma we drove to the historic center, which is a labyrinth of narrow, steep roads, and stone stairs cutting between houses. Along the main road were high pavements with ornate columns supporting open-balustraded galleries that sat in front of beautiful colonial buildings painted in soft tinges with ornate balconies and balustrades.

Outside the scenic center, however, the town was just as ugly and concrete. However, on the outskirts some people literally lived on gold. From the hilly roads we looked down on homes where people had their own little gold mines in the backyard. This gold mining is not a recent development. On the contrary: indigenous people mined gold in the region at least 3,300 years ago. Fittingly, the province is called El Oro (the Gold).

A Gold Mine

We met Tito, who took us to the mine of Miranda Alta, a place with history. When the Spaniards arrived here around 1536, they used the same route that we were taking to the mine, the difference being that at the time it was a forest path and now an asphalted road. After the Spanish came the Jews, the English, the French, and the Americans. They all came for the gold. Today the mining companies are Ecuadorian.

Outside the mine we talked to Saul, who had worked here since he was fifteen. He and his 35 coworkers were paid per month, which he preferred to the system where miners were paid according to the weight of the stones containing gold they had mined, which happened elsewhere in the area. Five to eight times a day they walked into the 500-meter-long mine that ran as deep as 200 meters. They dug the rock and filled up the burro, an iron cart that was then pushed back outside when if was filled with 250 kilos of rock.

The rocks were put in bags up to a weight of 40 kilos, and when there were 250 bags, a truck took these to the factory where the gold was extracted using mercury. Saul explained that many things had changed, such as the law on child labor. He had started working at the age of 15, but today you could only work in the mines from age 18, and miners worked 6 hours a day, contrary to 10 hours in the past. In earlier days you could dig anywhere; today you need permits. Of course, there still was illegal digging, but Saul knew of no stories of collapsing mines as a result of that.

A Banana Harvest

Related Articles

We said goodbye to Saul, thanking him for his time, and continued our route, following a country road that took us to Machala. Little by little we climbed a potholed road and reached the 2,100-meter Paccha Pass after which we meandered downhill again, this time into thick, grey clouds where the view was reduced to zero. At sea level the skies cleared, and we found ourselves in another world: green, humid and home to cacao and banana plantations. The cacao fruit was mostly red, dark purple; it would be another month before they were harvested. The bananas were all wrapped in blue plastic to keep insects away.

When glancing sideways, we spotted a group of people working on a plantation and stopped to see what they were doing. A man walked up to us and shook our hands. Carlos, the owner, offered to take us around, proud of his business. He grew up among bananas, his grandfather owned this plantation during the years that Ecuador was the largest banana producer in the world (1950s). Today, Carlos' son was learning the ropes. Some twenty men and women were working on the plantation. From trees heavy with bananas, one picker cut the big leaves away, freeing the stem so he could pull the whole bunch down using his elongated machete. His coworker put the bunch of bananas weighing 35 to 40 kilos on his shoulder and took it to the rail system, where he hung the bunch on one of the big hooks hanging from the rails. The network of metal arches ran through the entire plantation and instead of having to carry the heavy load, the worker could pull the hook with the bunch of bananas to the packing house, which obviously was much lighter work.

At the packing house, another worker took the bananas from the hook and measured them. If too big or too small, they were thrown back into the plantation to serve as compost. The bananas were then put into a bath with chemicals that would work on the skin to make it yellow, as well as make sure no insects stayed caught among the fruit. The last two workers packed the bananas in plastic in the all-too-familiar banana boxes. A truck was ready to leave for the airport from where they were going to their overseas destinations.

We thanked Carlos for the tour, climbed back into the Land Cruiser and hit the road once more, curious as to what else this part of Ecuador had in store for us.

To get your copy of the

Spring 2019 Issue:

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to get up-to-date industry news, events, and of course, amazing adventures, stories, and photos!